Subscribe to my Youtube channel at http://www.youtube.com/@revdrsusan.

Category Archives: Intrafaith

Explaining God in 9 Minutes

How would you explain your understanding of God, the Divine, Higher Power, or however you understand that which is bigger than ourselves? Are you apophatic (the so-called ‘negative’ approach, which means emptying the mind of words and ideas about God) or cataphatic (the so-called ‘positive’ approach, that uses words, images, symbols, ideas for the Divine)?

Are you a theist (for whom God refers to a being beyond the universe, another being in addition to the universe) or a panthentheist (for whom God does not refer to a being separate from the universe, but to a sacred presence all around us)?

And how would you convey your understanding to a person of a different religious tradition?

That is my assignment for the next two weeks. On August 18, the Peninsula Multifaith Coalition will hold a panel discussion that will explore the concept of God. Six different faith traditions will be represented, and I have the challenge of presenting the Christian understanding of the Divine in just nine minutes.

This is a daunting task and the intrafaith nature of such an endeavor is that there are numerous ideas about God within Christianity. I have always approached assignments like this by explaining that I could speak only for myself, not for every branch of the Christian tradition. As a progressive Christian who leans more towards the apophatic and panentheistic, I’ve found that I’m not always in alignment even with my Lutheran background. And this assignment will be even tougher. Our planning group wanted someone from within mainline Christianity to talk about – Dum Dum Dumm – the Trinity.

Oh, boy. Should I start off with the claim by theologian Karl Rahner that if the Trinity were to quietly disappear out of Christian theology, never to be mentioned again, most of Christendom would not even notice its absence! Probably not.

It’s not like I haven’t written and spoken about the Trinity. Looking back in my records, I can find a bunch of sermons and blog posts that deal with it. That kind of made me wonder why I’d spent so much time on a topic most of Christendom wouldn’t even miss. I mean, many progressive Christians have ditched it altogether. But I am one who is reluctant to throw out the baby with the bathwater. And there are some theologians, like Richard Rohr (The Divine Dance) and Cynthia Bourgeault (The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three: Discovering the Radical Truth at the Heart of Christianity) who have made the Trinity much more intriguing to me.

But how to approach it an interfaith setting – and in nine minutes? Do I go with the good old ice/water/steam analogy (very kataphatic)?

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Or a more apophatic image, conveying the unknowable Mystery?

You can probably guess which appeals more to me.

So I have an interfaith and an intrafaith dilemma. My understanding of the Trinity actually is very interfaith friendly. But it isn’t the mainline version.

I don’t have an answer yet. But as soon as I figure out what to do with my nine minutes, I’ll let you know.

Spiritual Fluidity

I was very interested when I learned that the book club of my area’s interfaith organization was reading When One Religion Isn’t Enough: the Lives of Spiritually Fluid People by Duane R. Bidwell. I hadn’t heard of this book, even though it was published in 2018. But I was intrigued because in my book, The INTRAfaith Conversation, I have a chapter entitled “New Voices.” And one of those voices is “Hybrid Spirituality: Multiple Belonging.” In it I quoted Francis X. Clooney, SJ:

The phenomenon of “multiple religious belonging” is now deeply engrained in American culture. We can no longer imagine simply the prospect of well-established religions and their members deciding whether to dialogue or not. People, younger people in particular, find themselves in the position of having multiple religious attractions, and experiences and commitments which cannot easily be fit into any given religious system.

For such people, it is unlikely that even upon ecclesial insistence they could give up strands of identity not easily reducible to a single tradition or church.

This obviously has huge implications for the church in the 21st century and we would be wise to pay attention to it.

I did learn (or relearn)some things from Bidwell’s book, beyond enjoying the stories he told of people living out their hybrid spirituality and resonating with his experience as an ordained pastor navigating the ecclesiastical institution as a hybrid.

First, was his statement “I do not believe that God is one or that all paths reach the same mountain.” This reminded me of Stephen Prothero’s book God Is Not One: the eight rival religions that run the world– and why their differences matter. I squirm when I hear interfaith friendly people declaring that “it’s all the same God” and “we’re all clinging the same mountain on different paths.” Even at a session of the Parliament of the World’s Religions, I was surprised when a speaker declared that we all worshipped the same God – especially when we’re also including people of no faith.

But I realized that I have preached about the one-ness of the Divine myself. A few weeks ago, when John’s gospel’s Jesus prayed “that we might all be one,” I played the music video “One” by Billy Jonas. It’s really a very cool video, but now I can see the problem in some of the lyrics.

One plus one

Plus one plus one

Makes ONE

One likes Jesus

One likes Judah

Yogananda, Allah, Goddess,

the Buddha!

Says ‘wait how do you pick a path?’

Solution: NEW new math

One plus one

Plus one plus one

Makes ONE

ONE-der where its leading to.

One-derful, wondrous thing

One way – the way we’re going.

One plus one

Plus one plus one

Makes ONE

It might not make a big difference when watching a video, but it’s something to think about.

The second thing I found interesting was Bidwell’s section called “Names Matter.” It reminded me of the explanation in my book of the dilemma of what to call the interfaith movement:

There is much ongoing discussion about what to call the movement. The Rev. Dr. Andrew Kille, executive director of the Silicon Valley Interreligious Council (SiVIC) writes that “interfaith carries some muddy implications that can be confusing – ‘interfaith’ organizations in the past meant ‘ecumenical’- all Christian, or, at best, Christian/ Jewish. It has also come to describe traditions that blend two or more religious observances into some whole. We chose ‘interreligious’ partly because the term is less familiar, partly because it suggests relationships between distinct traditions, rather than a blending of them. Multi-faith has much the same kind of sense about it. ‘Interreligious’ is also a term that hopes to include traditions for whom ‘faith’ is not really a meaningful concept- Buddhists, Wiccans, etc.”

Interfaith? Multi-faith? Interreligious? Multi religious? Pan-spiritual? Religio-pluralistic?

For the purpose of this book, I will usually use ‘interfaith.’

Now, Bidwell has added multiple religious belonging, dual religious practice, religious hybridity, to the list of problematic names and the challenge they entail. He chooses instead to use spiritual fluidity, religious multiplicity, and multiple (or complex) religious bonds.

For those of us who care about such things, it just goes to show the ongoing complexity of our religious/spiritual landscape.

And for those who don’t, there’s always

One plus one

Plus one plus one

Makes ONE

And maybe that’s OK.

INTRAfaith at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

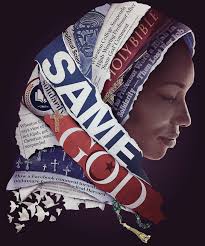

It’s been a long time since I’ve posted here. When last we met in January 2020, I was organizing a screening of Same God, the story of the Wheaton College professor who was removed from her tenured position because of her “embodied solidarity” with Muslims.

But then . . . well, 2020 happened. And it felt like a whole lot of other issues took center stage. I pretty much decided to give up on promoting my book, blog, etc. When I got the notice that the Parliament of the World’s Religion would be on line this year and was soliciting proposals for workshops at this years online gathering, I decided to give it a pass.

But, as is the way of the universe, something happened. I received two emails. The first was from members of FEZANA, a coordinating organization for Zoroastrian Associations of North America. They planned to propose a panel discussion on the need for Interfaith organizations to become incubators for intrafaith dialogue. They had somehow found me on the Internet and wondered if I would be interested. Of course, I was interested! That proposal was accepted and plans have begun for our presentation on “Tweaking the Interfaith model: Interfaith Organizations as Incubators for Intrafaith Dialogue.” More details will come as our planning proceeds.

The second email was from a retired Lutheran pastor in St.Paul, MN who had found my interview with Steve Kindle on Pastor to Pew about how to deal with John 14: 6: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me,” which John attributed to Jesus. Listen to that podcast here.

Rev. John Matthews had begun an initiative called the 14:6 Project. He says, “The exclusivity of this verse, while ‘understandable’ in its late-first-century historical context, hinders authentic dialogue with other faith traditions. The mission of the 14:6 Project is to focus on this verse of New Testament scripture that is so problematic for Christian involvement in interfaith settings.

He comes to these conclusions from a long career in this area. He was a founding member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) Consultative Panel for Lutheran-Jewish Relation (1990-2000), chaired the Region III (ELCA) Task Force for Jewish-Christian Relations (1990-2005), and served on the program advisory committee of the Jay Phillips Center for Interfaith Learning at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul (2004-2008). While on the ELCA Consultative Panel, Pastor Matthews assisted in drafting the “Declaration of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to the Jewish Community” (1994) which is now a part of the permanent display on anti-Semitism at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

Our workshop will be “A Deep Dive into One Barrier to Christian Interfaith Relations: Introducing ‘The John 14:6 Project.'” Our hope is to find others who want to continue the work of re-imagining this verse. We believe that If interfaith relationships are to thrive, each tradition must work on its own intra-faith issues. John 14:6 is Christianity’s intra-faith challenge.

So I’m back in. In fact, a third proposal, “Dismantling Patriarchy in the World’s Religions” was also accepted – but that’s the subject of another post. My commitment to the intra-faith conversation continues!

Same God Is Out! Go See It!

“Same God” – Embodied Solidarity Comes at a Price

“Same God” – Embodied Solidarity Comes at a Price

Back in 2016, I wrote two posts about Professor Larycia Hawkins, who was removed from her tenured position at Wheaton College because of her “embodied solidarity” with Muslims.

Wheaton College: an Intra-faith Controversy

The Professor Wore a Hijab in Solidarity – Then Lost Her Job:

An INTRAfaith Case Study

Then in 2018, I learned that there was a documentary about this intriguing story. So, of course, I wrote about that: Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God: More from Wheaton College

Now, it’s here! “Same God” is being shown this month on some PBS stations. Watch the trailer and find local listings here. There will also be a limited theatrical release beginning March 8. The best way to get information is to follow @samegodfilm on FB, Twitter, and Instagram.

“Same God” was directed by Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker Linda Midgett, who is herself a graduate of Wheaton. But make no mistake about it; this is not a defense of the institution. Nor is it a condemnation. It is a beautifully filmed, honest telling, not only of Dr. Hawkins’ story, but also of the history and current state and challenges of evangelical Christianity.

A Quick Recap

It really all started in 2013, when Dr. Hawkins (or Doc Hawk as students call her in the film) became the first female African-American tenured professor at Wheaton. At Wheaton, an explicitly Christian liberal arts college, all faculty members are required to annually sign a covenant which defines what it means to be “dedicated to the service of Christ and His Kingdom.” As the film tells us, Dr. Hawkins willingly and faithfully signed this covenant upon her employment and every year thereafter.

Then, on December 2, 2015, 14 people were killed in a terror attack in San Bernardino. Immediately, anti-Muslim rhetoric in the US began to ramp up. Then-candidate Donald Trump called for a Muslim travel ban. In response to this, Dr. Hawkins posted on her Facebook page that she was standing in solidarity with Muslims because they are also “people of the book” who worship “the same God.” As part of her Advent devotions, she posted a picture of herself wearing a hijab. That’s when it hit the fan. Long story short: she lost her job. The film covers all this very well, with interviews of Hawkins, plus faculty members and students. No one from the administration agreed to be interviewed.

A Rorschach Test

A Rorschach Test

There is so much in this film that could and should spark dialogue. Someone said that the picture of Dr. Hawkins wearing a hijab was like a Rorschach test; different people would see different things. For example, many Muslim women would see an act of compassionate solidarity (what Hawkins would call embodied solidarity). For others, it would surface questions about academic freedom, religious liberty, and theology. I would add that having seen the film, the picture is a stark symbol of the systems of patriarchy and white privilege at work. It’s also a reminder of the need for interfaith dialogue. The ignorance expressed in many of the reactions to Dr. Hawkins’ post is simply appalling.

What I see in the inkblot is an intrafaith conversation needing to happen.

To be sure, there are many facets to this story: blatant racism and sexism; the emotional toll of the entire saga on Dr. Hawkins; and not to be ignored, the career and financial hits she was forced to take. All of these are very worthy of our attention. But what caught my intrafaith eye was the hurt she experienced in being accused of not being Christian. In a review in the Chicago Tribune, Linda Midgett expressed hope that her documentary will spark dialogue between people of different faiths so they can find common ground. I wholeheartedly agree! But I also hope it will encourage dialogue between people within the same faith – in this case Christianity.

It Really Is about Theology . . .

In the film, Dr. Hawkins says that the controversy in which she was embroiled was not about a theological debate. In the context of her grilling by the Wheaton provost, I agree and applaud her courage in naming what was unfair in the process and her refusal to engage in further “theological conversation.”

Having said that, it is clear that theological questions loom large over the whole saga. Dr. George Kalantziz, Professor of Theology, hits the nail on the head: “When we ask the question ‘does Islam (or any other religion than Christianity) worship the same God?’ it’s always a qualified ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ We don’t all understand the word, not only ‘God,’ the same way, but worship the same way.”

Bingo! Wheaton missed an opportunity to explore these questions.

And Even More So, Christology . . .

I’m particularly interested in the Christological questions raised by the firestorm of responses to Dr. Hawkins’ assertion that Muslims and Christians worship the same God. In the film, as Dr. Kalantziz is speaking, the camera pans across a beautiful church sanctuary. In the foreground is a gold processional cross. The symbolism is unmistakeable: this is a place that worships Jesus the Christ. Although never explicitly stated in the film, this is the heart of the matter. Who was/is Jesus? How does belief in Christ as the second person of the Trinity inform our beliefs about the truth of other religions?

The interview with Bishop David Zac Niringiye would be the perfect discussion starter on how our interfaith encounters inform/strengthen/challenge/change our own beliefs. Speaking eloquently of the need for Christians to listen to our Muslim siblings, he says, “There is something about what they know of God that might cause me to understand God more.” He goes on to qualify: “Now, it is true, that the revelation of God is finally in Jesus Christ. It is complete.”

There is where I’d want the conversation to begin.

“Your Christianity Isn’t Real”

One of the most heartbreaking aspects of Dr. Hawkins’ story is the fact that her identity as a Christian was called into question. I can relate to a point. My job was never on the line. But I know that my adherence to orthodoxy has been questioned. In my case, it’s because I’ve moved further into Progressive Christianity, which has major differences with more traditional ways of believing. The ironic thing here, though, is that Hawkins is quite at home in evangelical Christianity. In the film, she movingly speaks about her baptism in her grandfather’s church, her love for Jesus and how that informs her work in the world. An interesting aspect of the film is its contrasting of African-American and white evangelicals. I was reminded that ‘evangelical’ does not describe a monolithic group; we on the more liberal side should not use the term irresponsibly.

I’m part of a denomination with ‘evangelical’ in its name: The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. We often have discussions about removing the ‘evangelical’ part because we don’t want to be identified with what has become white evangelicalism since the 1970s (this was a really helpful part of the documentary). Listening to Wheaton faculty members, it’s clear they’re having some of the same dilemmas. I believe we could easily find some common ground in an intrafaith dialogue.

Who Are We? Christian Identity in the 21st Century

Most religious groups are undergoing a time of questioning about their place in the world. This is causing great anxiety among many people and institutions. As Dr Kalantziz said, “Questions have moved. People, ideas have moved . . . expressions of theology have changed.” This is not good news to many who are resistant to change, especially in theology and religious practice. He talks about the evangelicalism of the past and the future, about two kinds of leadership: pioneers and overseers. The role of overseers is to keep the heritage of American evangelicalism alive.

Wheaton College, despite its pioneering history as a stop on the Underground Railroad, has become an overseer, dedicated to an evangelicalism of the past. Larycia Hawkins, on the other hand, can be seen as helping to usher in an evangelicalism of the future. That’s obviously not an easy place to be. The film poignantly allows us to enter into her life – in the courage, strength, conviction, and resilience, as well as the vulnerability, suffering, and loss. I don’t know how anyone could fail to be moved by her story.

My interest in Dr. Hawkins began as a rather academic exercise in showing an example of an intrafaith issue. Having seen the film, I’m even more of a fan – of the person and her witness of faith in action. It’s still an intrafaith story, but so much more. I hope it will be seen by Christians, from evangelicals to progressives. And I sincerely hope that director Linda Midgett’s vision of her documentary sparking dialogue will be fulfilled: both between people of different faiths and between people within the same faith.

https://www.facebook.com/samegodfilm/

https://twitter.com/samegodfilm/

https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/samegodfilm/

You Might Be a Christian Atheist If . . .

New Voices . . .

New Voices . . .

is a chapter in my book, The INTRAfaith Conversation, in which I describe some of the groups now included in the interfaith scene.

These groups include . . .

Atheists and Humanists

Since the book was published in 2015, there have been a lot of new developments. I was aware of the wide range of definitions for atheists and humanists when I wrote the book. Since then, I’ve been fascinated by the further exploration, expansion, and definition of these terms. I’m not much interested in the fundamentalist atheists, who are just as dogmatic as the religionists they criticize. But I am drawn to those who are exploring the boundaries of who and what God (or Being or Presence or no word at all) is.

Probably the most public lately has been Gretta Vosper, the self-professed Atheist who is a pastor in the United Church of Canada (I wrote about her in Should the Atheist Pastor Be Defrocked?). In 1997, four years into her call to West Hill United Church in Scarborough, Ontario, she preached a sermon called “Deconstructing God.” At that point, she defined herself in a more “not this” manner, declaring that she did not believe in a theistic God. Then in 2013, she moved from non-theism to atheism after she read about the plight of Pakistani bloggers who faced punishment as blasphemers for questioning the existence of God. For her (according to her website), “god is a metaphor for goodness and love lived out with compassion and justice, no more and no less.”

In 2017, I met Carrah Quigley when we presented a workshop together at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Toronto. Carrah identifies as a Spiritual Humanist. According to the Church of Spiritual Humanism, this is a “religion based on the ability of human beings to solve the problems of society using logic and science . . . using scientific inquiry we can define the inspirational, singular spark inherent in all living creatures.” Spiritual Humanism is natural, not supernatural.

Atheists for Jesus?

Atheists for Jesus?

Then, just this month I came across the category of Jesus-following Atheists (also known as Christian Atheists) in an article entitled Inter-faith Dialogue with Christian Atheists.

Hmm. Intriguing.

From what I’ve read, it seems that the main focus of Christian Atheism is the life of the historical Jesus and the system of ethics drawn from his teachings. Although, regarding the subject of God, there is some divergence. While some do reject the idea of God altogether, others dismiss the belief in a supernatural, interventionist God. According to the author of What Does It Mean to Be a Christian Atheist?, “I still believe in ‘God.’ What I do not accept is belief in a theistic deity, a ‘being’ that created the universe, holds the universe together, or exists in or apart from the universe.”

Of course, Bishop John Shelby Spong has written and spoken much about the death of theism, and I greatly appreciate his insights about coming to reject the belief in a supernatural power. I don’t think he calls himself an a-theist; he’s more inclined to dismiss as inadequate these words for our experiences of the Divine. The experience is what is important. In this sense, I have no qualms about calling myself an a-theist. Especially since he doesn’t reject the reality of mystical experiences of the Holy, as do some who adhere only to the ethical teachings of Jesus.

However, at the end of the day, I still resonate most with Teilhard de Chardin’s panentheism, in which all creation exists within a ‘divine milieu.’

Still, I am intrigued by the ongoing exploration of what we mean when we think about God (the Divine, Spirit, or no name at all). The freedom to go outside the bounds of our traditional (and limited) understandings enhances not only our own spiritual/ethical life, but our communal life as well.

The interfaith world benefits from the presence of those who do not fit the definition of “religion.” The intrafaith scene can benefit as well, if we get past our prejudices (especially when we don’t know the broad range of these groups) and listen to their stories.

“I am the way and the truth and the life” at Churchwide Assembly

This past week, my denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), held its triennial Churchwide Assembly. One of the main events was voting on the proposed policy statement: A Declaration of Inter-Religious Commitment. I’m proud to say that it passed 890-23.

This past week, my denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), held its triennial Churchwide Assembly. One of the main events was voting on the proposed policy statement: A Declaration of Inter-Religious Commitment. I’m proud to say that it passed 890-23.

That might have been due to the fabulous array of ecumenical and inter-religious guests!

There was, however, one moment of concern from the intrafaith perspective. An amendment had been submitted calling a section of the policy statement “inconsistent with Scripture,” which proposed striking some of the language of the statement under the heading “Limits on our knowing” (lines 630-655). The author of the motion based his challenge on our old friend John 14:6, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

In the amendment he wrote: “We have a clear statement from Jesus, who is fully God and fully man. We do therefore have a basis to know God’s views on religions that do not require faith in Jesus Christ as God’s son.”

In the amendment he wrote: “We have a clear statement from Jesus, who is fully God and fully man. We do therefore have a basis to know God’s views on religions that do not require faith in Jesus Christ as God’s son.”

Speaking from the floor, he added: “I am here to speak truth to power, even if it is an inconvenient truth. I would urge this assembly to repudiate and repent of any false teachings.”

The only other person who came to a microphone stated, “I’m embarrassed that we’re having this conversation in front of our interfaith guests.”

The motion to amend was overwhelmingly defeated and the policy statement was adopted.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am delighted that this policy statement has been adopted. But I’m also disappointed that this very appropriate question was not adequately addressed. To be fair, I doubt that it could have been adequately addressed in the context of the amendment’s discussion time. And I have to wonder how many other voting members had similar questions but not the courage of this one lone amendment-maker. Having the discussion with all the interfaith guests standing right there on the stage might not have been an embarrassment, but it sure might have been a deterrent.

As I have said innumerable times, the “What about when Jesus said . . .” question has come up in virtually every interfaith workshop I’ve ever led with Christians.

Here is an audio version of the interview I did on Pastor to Pew a few years ago. We talk about my book, The INTRAfaith Conversation. But mostly it’s my take on John 14: 6 and how taking the intrafaith question seriously is a necessity for today’s church.

Presiding Bishop Eaton said (in reference to our ecumenical relations) that “ecumenism is not an add-on, but a central part of what it means when we say we are church.” I know even that’s a stretch for many congregations, but I wish that our inter-religious relations could also be central to what it means to be church.

But if we do take interfaith seriously,

we’re going to have to also take intrafaith seriously.

Thankfully, there’s a resource for this! (Shameless self-promotion warning)

“. . . meeting and respecting a person of another religion confronts us all with the question raised by Marjorie Suchoki in Divinity and Diversity:

Our Christian past has traditionally taught us that there is only one way to God, and that is through Christ. But we are uneasy. Our neighborliness teaches us that these others are good and decent people, good neighbors, or loved family members! Surely God is with them as well as with us. Our hearts reach out, but our intellectual understanding draws back. We have been given little theological foundation for affirming these others – and consequently we wonder if our feelings of acceptance are perhaps against the will of God, who has uniquely revealed to us just what is required for salvation.

“As pastors and lay leaders we are responsible to our congregations to provide the theological foundation for affirming ‘these others.’ Rather than succumbing to what John Cobb calls ‘the danger that sensitive Christians will simply delete central beliefs rather than transform them,’ I believe that we have some serious theological and Christological work to do in defining, or perhaps re-defining, ourselves in light of our interfaith milieu.” (The INTRAfaith Conversation, Introduction)

I really hope we take up the challenge to build relationships with our inter-religious siblings. I also really hope that we’ll also take up the challenge to engage folks like the writer of the amendment. That’s not an add-on either, but should be part of what it means when we say we are church.

then intrareligious dialogue must accompany it.

– Raimon Panikkar

What to Do with “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life”?

In virtually every workshop I’ve ever led about interfaith matters, someone asks the question: “What about when Jesus said, ‘I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life. No one comes to the Father except through me?”

Here is an audio version of the interview I did with Steve Kindle of Pastor to Pew a few years ago. We talk about my book, The INTRAfaith Conversation. But mostly it’s my take on John 14: 6 and how taking the intrafaith question seriously is a necessity for today’s church.

You can also see the video here.

Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God: the Pope Said So!

1219 CE: St. Francis and the Sultan

1219 CE: St. Francis and the Sultan

This year marks an important date in interfaith history. Eight-hundred years ago, as Christians and Muslims were in the midst of fighting the fifth crusade/jihad, St. Francis of Assisi had a remarkable visit with Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil of Egypt. You can read more about that historic event here.

What I really want to talk about is another, much more recent, historic meeting. Last month, Pope Francis visited Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, and met with Sheik Ahmad el-Tayeb, the Grand Imam of Egypt’s Al-Azhar mosque. What transpired is just as momentous as the meeting of St. Francis and the Sultan.

2019 CE: The Pope and the Imam

On February 4, Pope Francis and Sheik el-Tayeb signed a document on improving Christian-Muslim relations called “Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together”.  It begins:

It begins:

In the name of God who has created all human beings equal in rights, duties and dignity, and who has called them to live together as brothers and sisters, to fill the earth and make known the values of goodness, love and peace . . .

By beginning this way, the document (hopefully) puts to rest the idea that we do not worship the same Deity, whether we call that Deity God, Allah, Ground of our Being, or Nameless One.

The really stunning part comes two-thirds of the way down. Tucked into a list of convictions essential for upholding the role of religions in the construction of world peace, is this statement:

The pluralism and the diversity of religions, colour, sex, race and language are willed by God in His wisdom, through which He created human beings.

(I know. I have to temporarily suspend all of my convictions about exclusively male language for God. But the implications of the statement are too big to ignore.)

It’s Been Done Before

While potentially provocative, it’s not the first time the Catholic Church has made such a declaration. In 1965, the Second Vatican Council approved Nostra Aetate: Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions. Regarding Islam, it said:

The church also regards with esteem the Muslims. They adore the one God, living and subsisting in himself, merciful and all-powerful, the Creator of heaven and earth.

Remember the brouhaha at Wheaton College a few years ago when one the professors was fired for wearing a hijab in solidarity with Muslims? It was also about quoting the Pope: “As Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.” Her reference was to: Meeting with the Muslim Community at the Central Mosque of Koudoukou, Bangui (Central African Republic) on November 30, 2015.

Remember the brouhaha at Wheaton College a few years ago when one the professors was fired for wearing a hijab in solidarity with Muslims? It was also about quoting the Pope: “As Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.” Her reference was to: Meeting with the Muslim Community at the Central Mosque of Koudoukou, Bangui (Central African Republic) on November 30, 2015.

Pushback!

There has been criticism of these pronouncements. In 2000, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger issued a warning about the danger of “relativistic theories which seek to justify religious pluralism.” In “Dominus Iesus,” the future Pope Benedict XVI said

This truth of faith (that Christ is the salvation of all humanity) does not lessen the sincere respect which the Church has for the religions of the world, but at the same time, it rules out, in a radical way, that mentality of indifferentism “characterized by a religious relativism which leads to the belief that ‘one religion is as good as another.

Of course, the Protestants also got into the act. Hank Hanegraaff, known as the “Bible Answer Man” on his radio show has said that “the Allah of Islam” is “definitely not the God of the Bible.” And the evangelical Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry unequivocally states that Christians and Muslims do not adore the same God, and that the Catholic Church has “a faulty understanding of the God of Islam.”

Now granted, these are positions from the Catholic Church and evangelical Christianity. I have problems with both sides on issues other than this one. But I applaud the efforts of Pope Francis to further our interfaith awareness and acceptance.

What Does Progressive Christianity Say?

As a progressive Christian, I agree with the second point of The 8 Points of Progressive Christianity:

By calling ourselves progressive Christians, we mean we are Christians who affirm that the teachings of Jesus provide but one of many ways to experience the Sacredness and Oneness of life, and that we can draw from diverse sources of wisdom in our spiritual journey.

By calling ourselves progressive Christians, we mean we are Christians who affirm that the teachings of Jesus provide but one of many ways to experience the Sacredness and Oneness of life, and that we can draw from diverse sources of wisdom in our spiritual journey.

The INTRAfaith Conversation

Agreeing to this statement, though, doesn’t mean I don’t recognize the dilemma that exists within these statements, pro and con. I give Cardinal Ratzinger just a tiny bit of credit because he attempted to engage the elephant in the living room: what about Jesus? I don’t agree where he comes down, but he did engage the question. Pope Francis and Sultan al-Malik al-Kami didn’t get into knotty questions, such as the divinity of Jesus or the Trinity.

They were all about peacemaking – and props to them for that!

It is left to us to wrestle with our inherited Christologies (as well as doctrines, creeds, liuturgies, hymns, prayers, etc.) in light of our desire to live in peace and harmony with our religious neighbors. As Kristin Johnston Largen wrote in Finding God Among Our Neighbors, “. . .issues of Christology cannot be avoided in an interreligious conversation that professes to take Christian faith claims seriously.” In other words, who/what is Jesus in an interreligious context?

It is left to us to wrestle with our inherited Christologies (as well as doctrines, creeds, liuturgies, hymns, prayers, etc.) in light of our desire to live in peace and harmony with our religious neighbors. As Kristin Johnston Largen wrote in Finding God Among Our Neighbors, “. . .issues of Christology cannot be avoided in an interreligious conversation that professes to take Christian faith claims seriously.” In other words, who/what is Jesus in an interreligious context?

Such wrestling is what I attempt to facilitate in my book, The INTRAfaith Conversation: How Do Christians Talk Among Ourselves About INTERfaith Matters?

Pope Francis and the Imam have given us a lot to think about.

Let’s talk!

ELCA’s Inter-Religious Commitment

One of the workshops I attended at the Parliament of the World’s Religions (PWR) in November was At the Intersection of Ecumenical and Inter-Religious Relations. One of the reasons that session appealed to me (among the 15+ other offerings at the same time) was the moderator of the panel was Kathryn Lohre, executive for Ecumenical and Inter-Religious Relations for my denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA)

Intersection of Ecumenical and Inter-Religious Relations. One of the reasons that session appealed to me (among the 15+ other offerings at the same time) was the moderator of the panel was Kathryn Lohre, executive for Ecumenical and Inter-Religious Relations for my denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA)

She is also one of the members of the task force that created Inter-Religious Commitment: A draft policy statement of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. This is a new social statement that will be considered at our national church gathering this coming August.

Here’s the PWR workshop description – and if you’ve read my book or anything else on this blog, you’ll understand why it was right up my alley (bold type is mine):

In the midst of rapid changes in our global religious landscape, Christian churches, denominations, and councils of churches are increasingly exploring what it means to be Christian — and to seek Christian unity — in a multi-religious world. New approaches to interreligious relations are emerging, and focus is being given to understanding complex forms of religious and spiritual identities, practices, and communities. All of this is raising important and timely questions about the challenge of Christian supremacy in interreligious spaces and relationships.

One of my gripes about the Parliament is that there’s never enough time to really engage in a topic after a workshop or presentation. The conversation that began after this one could have gone on for hours. Although unfortunately it got sidetracked by a couple of guys, members of non-Christian groups, who thought it necessary to “mansplain” how we Christians could get around our issues. By the time I got to ask my question, our time was almost up.

What I wanted to know was this: how are the interfaith departments in our denominations working with other departments to promote the idea that interfaith – and of course I’ll also emphasize intrafaith – engagement is not simply an add-on to all the other work that goes on in our churches? Understanding our religious diversity – and our response to it – is a necessity for our work in Christian education, evangelism, seminary training, to name a few. Most of the clergy I know are overwhelmed with the day-to-day stuff that leading a congregation entails.

Plus, in the midst of the down-sizing of the Christian church, many congregations are anxiously trying to figure out how to stay open. Interfaith dialogue seems to be a luxury they cannot afford. But my premise is that it is not a luxury. In fact, as the church learns how to be present in the 21st century, albeit smaller, it will have to add interfaith and intrafaith engagement to its toolbox.

So I’m excited about the upcoming presentation of Inter-Religious Commitment: A draft policy statement of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America at our Churchwide assembly in August. Although I do have some questions, as well as suggestions for implementing the document. But that another post. Stay tuned.